By Bob Fish

Sorting coffee can be a mucky, dusty business in the best of circumstances. But we were in Lusaka, the Capitol of Zambia where the circumstances are far from ideal. Consider this: a whopping 60% of Zambians live below the poverty line, and 42% would be considered extremely poor. It’s not that there aren’t economic opportunities in Zambia, but the challenges are large, too. For one thing, it’s a land-locked country. Unless it goes by air (which is very expensive), everything that they export and import must cross somebody else’s border.

So, although Zambia backs up to coffee ‘heavy weight’ Tanzania with similar attributes for producing quality coffee, it is lessor known as a producer because it is just that much harder (and more expensive) for Zambian coffee to get to market. Of course, the government has been a little ‘off course’ too in its support of the industry, but the fact that the coffee must cross another country’s border to get to a harbor complicates things tremendously.

I believe that Capitalism, particularly Conscious Capitalism, is the best way to end poverty in any country, and any way we can help promote that idea is a plus. So there we were, standing in a dusty coffee processing plant in Lusaka.

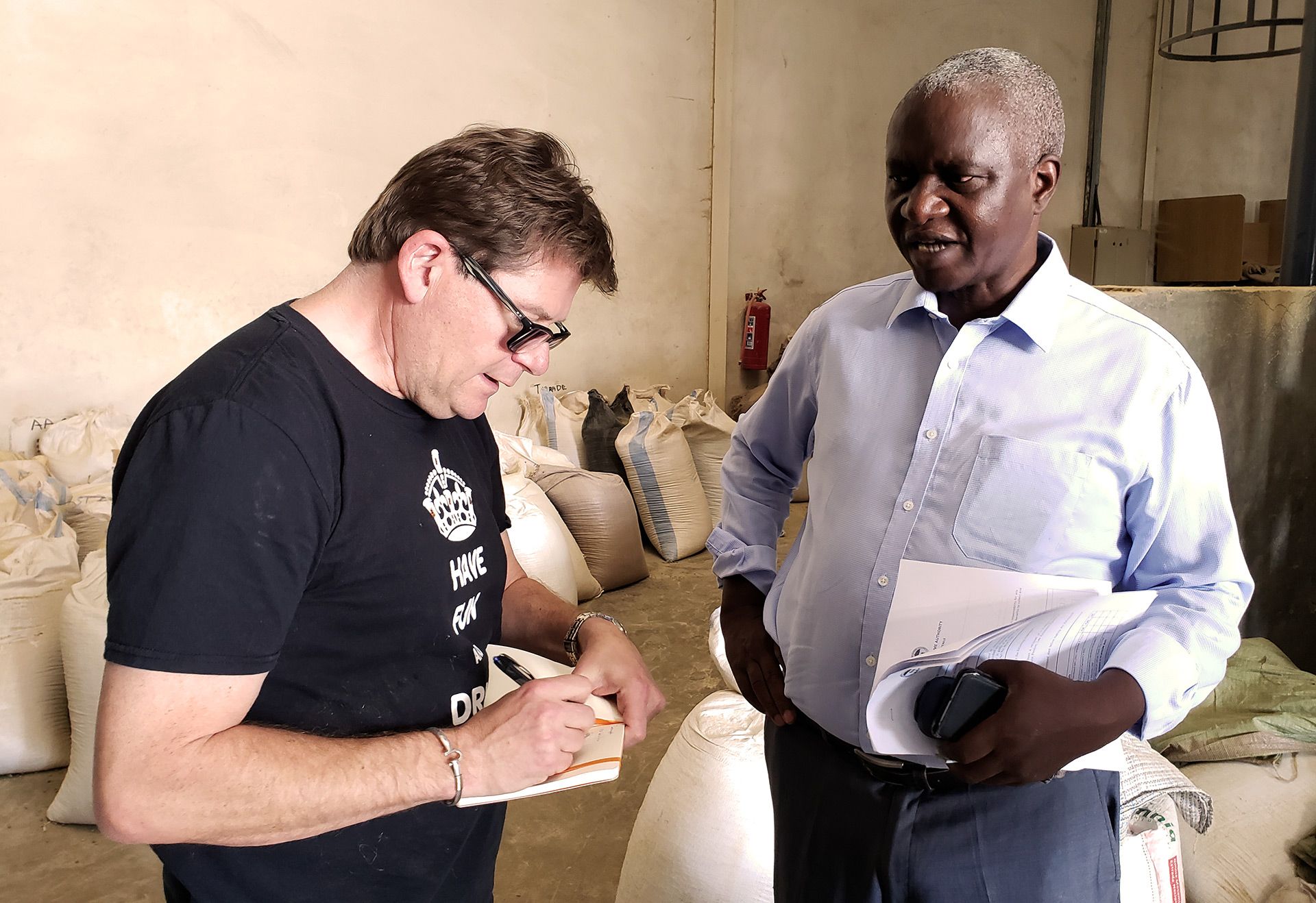

There are many steps to processing coffee from seed to cup. The first steps are done on the farm… planting, harvesting, processing the cherries, and drying. In Lusaka we were focusing on the hulling, grading, and sorting of the coffee (seeds) beans. We had the opportunity to meet with the Zambian Coffee Growers Association and they took us over to their facility to watch our Zambian Coffee get processed.

We noticed right away that while men were in charge of the plant, it was mostly women who did the work. A burlap bag of coffee is awkward to handle at around 120 pounds, and the women were hard at it. Another sight that got our attention: the number of particles floating in the air, to the degree that you might think you were in a snow globe. No such thing OSHA or the Health Department. Seemed the farthest from anybody’s mind because the sides of the building were open and safety around the machinery or air quality just did not seem a concern. Now all that sounds bad, but in context it seemed normal, safe, and sanitary. I had no concerns, but it does make you consider how fortunate we are back in the States. We often complain about regulation in business, until you see what it looks like with no regulation. We could walk freely throughout the facility ask questions and learn about the equipment for processing for shipping.

The actual hulling, sorting and grading were all caught on video by Michelle, and if you want to understand what that looks like take a moment to watch each of them. Keep in mind Michelle and I are learning videography on the fly, and so the sound and video quality is fairly poor, but these will certainly give you a decent overview of what we experienced.

Just to add a little more context though, hulling is when the parchment layer is taken off the bean. Sorting and grading, on the other hand, use two different machines: one which vibrates and sorts the beans for density, and the other which measures for size. The nomenclature for grading varies per country but Zambia uses the same system as Kenya. You might have heard of Kenya AA (double a), and there is triple-A and single-A also, as well as about 9 other grades. This system would not be that different from how we look at egg grading in the States. Consistent size (and grade) are important to the roasting process. For example, if you put different size beans in a roasting chamber and fire them up to 420 degrees the small one will burn before the big ones are done. If they are all the same, they will roast evenly together.