By Michelle Fish

Prologue

Bob and I get asked all the time how we find producers that meet our criteria: doing the right thing for their people, for the planet, and for their communities. I understand why people ask, and why they look at us sideways when we tell them.

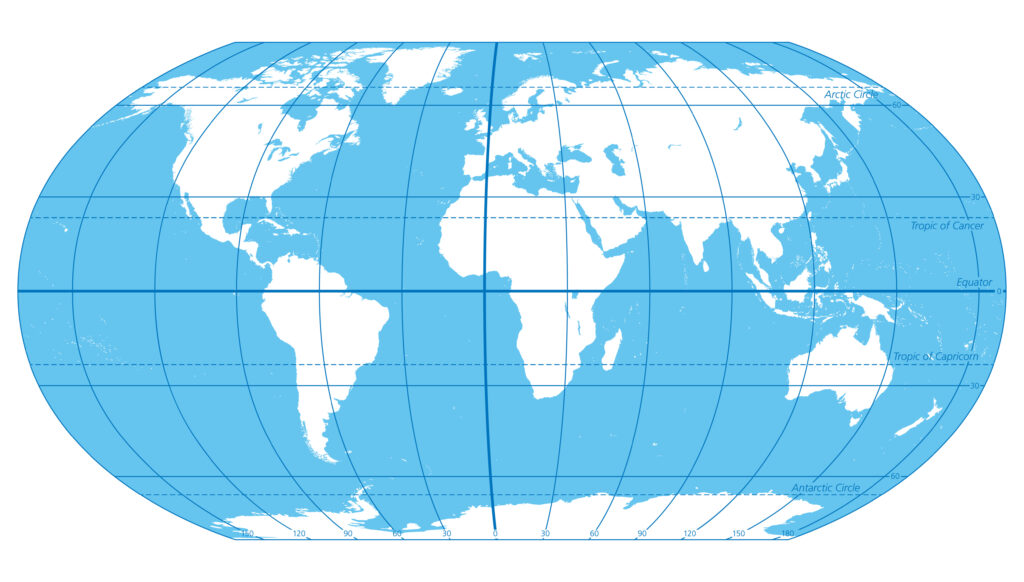

Coffee is grown all over the world, at altitude, in a band above and below the equator, between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn.

More than that, it’s grown in a multitude of countries that most people have never visited, or maybe even heard of. Or, if they know of the country, what they’ve heard is that it’s not safe to be there because of war, political instability, or a lack of basic infrastructure.

That’s a very large gap to bridge for two middle-aged white people who live in Michigan, USA.

So how do we do it?

How we started

Back in 2018, at the beginning of our OBIIS journey, we searched every haystack we could think of for a needle. Every trade show we could go to. Every friend of a friend we could reach out to. Every like-minded soul doing similar work in the world that we could love-bomb with questions.

*Bob at the Specialty Coffee Association Tradeshow in Boston in 2019.

We accepted an audacious goal from BIGGBY COFFEE: We would 100% change the way BIGGBY COFFEE sourced its primary product by 2028, moving to a Farm-Direct model. It was – it is – a moonshot.

We had no idea, really, how to do it. But we started anyway. And we’ve been figuring it out as we go. My husband has a saying… iterate and reiterate. I can tell you from lived experience, it works.

Because as I write this, we’re about 35% of the way to our goal, and on track to be 50% before the end of 2024. Not bad, when you factor in two years lost to COVID and family health issues. We’ve travelled hundreds of thousands of miles and met all kinds of people along the way.

It’s about the people

And that’s the key…. Meeting people. Because the more people who know what we’re up to in the world, the more people we find that want to help us get there.

After five years at it, we are in the fortunate space of having people reach out to us. These are people who have a connection to someone trying to do something important and good with coffee. We always listen, and we always go in with a wide-open mind about the opportunity.

They don’t always work out. At least, not initially. And sometimes, what we find breaks our hearts. But we won’t stop going. And we won’t stop chasing down improbable leads.

After all, coffee starts as a seed. It can take a coffee plant three years to become a commercial crop. And hope starts as a seed, and so does opportunity.

This is a story about something that might go either way. Maybe it comes to nothing, maybe it changes the world for people in the remote “upcountry” of a place in West Africa that could really use a few seeds of hope. Here’s how it started.

The Connection

BIGGBY COFFEE is 100% franchised. And with 360 units (as of this writing), you can probably guess that there are a lot of franchisees.

It is also a company that leads with its values. That means it attracts some amazing, inspiring entrepreneurs (franchisees) that are committed to a different way of doing business: capitalism that creates a win-win for everyone in the chain. You can read a lot more about that here.

One of those franchisees is Jonathon Sell. He’s the reason we went to Sierra Leone. He’s also a rock star in terms of being an amazing human. Perhaps because he comes from good stock. His dad, a doctor, had done a lot of work in Sierra Leone, a desperately poor country in West Africa.

The Context

It was once a colony of the Portuguese and there is a long history of exploitation and repression that still reverberates today. Here’s a link to the Wikipedia page, in case you want to know more.

More recently, it endured a brutal civil war in the late 1990s/2000s. And then an Ebola outbreak in 2014. Both reshaped the country in ways that they are ill-equipped and still struggling to deal with. There were mass movements of population from the rural areas to the capital of Freetown. In the upcountry, the traditional repositories of knowledge either died or moved away.

That sounds less impactful than it is.

Imagine that you live in a place with no experts. No doctors, no scientists, no engineers, few teachers. And then, imagine that you live in a place with even fewer grandmothers (mostly widows), no grandfathers, no institutional repositories of traditional knowledge. No one to tell you that you should feed a cold and starve a fever. Or what to give your child if they have intestinal distress.

And then imagine that place has zero resources to change its plight. Few viable crops to sell, no industry, high rates of illiteracy, and no government infrastructure to lean on.

Once, it produced a small but mighty middle class. And those people made sure that their children got a great education. It is that class of kids, now in their 40s and 50s, that have come back to be in roles of service, whether that’s in the government, or working for NGOs, or doing what they can from the United States.

*Kadiatu Allie

Kadiatu Allie

That’s where Kadiatu – or, as we call her, Kadie, comes in. She’s from the upcountry. She got a great education in Sierra Leone. After earning her bachelor’s degree, she had the opportunity for a scholarship for a year at Kalamazoo College (where our son went, and so did Bob’s business partner, Mike McFall). And then, she got a scholarship to pursue an advanced degree. And then she got a job for a multinational corporation.

She also married a guy from Sierra Leone who has a similar background and a similar trajectory. She has a big job with BP, her husband Emmanuel worked as a teacher and at IBM. But although they’ve made a life together in the US, their hearts are with their people in Sierra Leone. In fact, her husband moved back there recently to work with an NGO that is helping the Government to completely revamp their education system.

Kadie never, ever, stops thinking about the needs in her country, and about the many ways her comparative good fortune can create connections that can make things better for her people.

Access to medical care is just about non-existent in the upcountry. So, she chased down US connections to find doctors who could come for extensive in-country clinics. That’s how she found Jonathon Sell’s dad. After several medical missions together, they became close friends.

She told him that she had been hearing a lot from some of her extended family in the region that farm coffee. They were complaining about the traders, and how they paid so little for their crop that they could barely afford to feed their families. He suggested that she speak to Jonathon. And he put her in touch with us.

Making a Plan

We had several zoom calls with Kadie in the Fall of 2022. We liked her right away. She’s smart, funny, warm, and big-hearted. And she is brimming with passion for the plight of the people in the villages where she’s from.

As a way to help, she and her brother started a business a few years ago processing and importing sustainable red palm oil. She pays above market prices to the producers in her region, and then imports it to the U.S. She finds a market for it here, mostly to African grocery stores in and around Chicago.

Her grandfather had been a coffee farmer, so the story of coffee was something she had grown up with. He had done well enough to have several permanent employees, a car, and enough money to make sure his kids were educated. Now, she has an uncle and many first, second and third cousins that are still trying to make a living in coffee. But the landscape has changed completely.

In most coffee producing countries, you’ll find a merchant class that stands between the small producers and the market. And sadly, in most places where there’s a gate-keeper, it’s not the farmer who wins.

Kadie told us that most of these farmers are illiterate and struggling. They are paid far below market prices for their crop. In many cases, they are being straight up cheated. Sometimes, because they need to feed their families before harvest, they will take an “advance” on their crop in the form of a bag of rice. And when it’s time to sell their crop, the traders will take one bag of coffee for each bag of rice they advanced. The only problem is that coffee is worth six or seven times more than rice. But the farmers have no choice, because they don’t have direct access to a larger market.

She encouraged us to come and see for ourselves. Some of our best Farm-Direct contacts have been with U.S.-based family members of coffee producers. And Kadie had already figured out a pathway to import an agricultural product here. Our values were aligned and we liked her. So YES, we were excited to go.

*Meeting up with Jorge Ferrey Machado and Nathan Havey at the Charles de Gaulle airport.

The Journey

It’s a long way to Freetown, Sierra Leone. Bob and I flew from Chicago to Paris, where we met up with Jorge Ferrey Machado, our Farm-Direct partner from Nicaragua, and Nathan Havey, our friend and cinematographer.

From Paris, it’s another eight hours to Lungi International Airport, across the bay from Freetown, the capital. Then a bewildering maze of immigration and customs. Then a half hour boat ride across the bay to the capital city.

After all those hours trapped inside airplanes, sitting on the deck of the boat with the wind whipping around us and the sound of the waves was delicious.

*The first glimpse of Freetown from the boat ride ride from Lungi International Airport.

We came in at night, and as we drew closer to the city, thousands of lights twinkled on the hillside. The closer we got, the stronger the smell of burning. Some of those twinkling lights were fires, burning trash and burning plastic. It’s an acrid smell that followed us everywhere in the city.

We were met at the dock by Kadie with hugs, smiles and a big basket of oranges. And we trundled off in her car to make the climb to her city house. She fed us a wonderful meal of rice and spicey stewed vegetables. Finally, we collapsed into our rooms. Kadie told us not to get to too used the air-conditioning, because we weren’t going feel it again for several days. She wasn’t kidding.

Getting there

If J. Alfred Prufrock measured out his life in coffee spoons (T.S. Eliot), then ours can be understood as a series of bumpy, snug rides in SUVs. Three of us in the back, two up front, and a trunk full of backpacks, carry-ons, and cases of bottled water. We bounce, jiggle, and smash into each other for hours at a time. It’s not comfortable, but it’s not terrible either. And it sure builds a lot of intimacy and team bonding in a big hurry.

*Learning the Sierra Leonean way to eat oranges with Kadie in the back of the SUV.

That’s how we started our drive to the upcountry in the back of Kadie’s SUV.

But first, we had to snake through the bewildering backstreets of Freetown. It was built to be a city for 1/10th of the population that currently inhabits it. Any urban planning has been completely swamped by the sheer volume of people escaping war, Ebola, and abject poverty in the rural areas.

Freetown

I cannot adequately convey the scale of the pandemonium that is Freetown. It’s like a fever dream. So many people, so many cars, and no obvious ground rules for who should be where. For every one car, there are 20 mopeds, zipping in and out. Street vendors in the road, hawking food and cell phone chargers. Pedestrians launching themselves into the oncoming traffic. And everywhere, there is the smell of burning.

Kadie told us that the city looked completely different when she was a child. It was once surrounded by lush forests and multiple rivers. She can remember climbing up into the woods to pick fruit. There were people fishing. It was clean, and it was beautiful.

But with the pressure of rapid population growth, first the forests disappeared. And then, because the trees were gone, the rivers dried up. People built shacks in the dried out riverbeds. Everywhere you look, there are makeshift houses in improbable places on the hillside.

*Arial view of the ramshackle and very vulnerable housing built to accommodate Freetown’s burgeoning population.

There is pipeline that runs several miles up the hill to Kadie’s house, providing water for those neighborhoods. “Squatter” shacks have been built along side the pipeline, jammed in one after the other for the entire length of the pipe. Literally tens of thousands of people who couldn’t find any other kind of shelter, so they created these little shacks out of whatever materials were at hand. And they illegally tap into the piped water. As you can probably guess… there’s no water left in the pipe.

Sierra Leone is very near the equator. It has two seasons: hot and wet, then hot, dry, and dusty. With no trees, there is little respite from the heat in the city. So much so that the Government in Freetown has created a new position: A Minister of Heat, to help combat the worsening changes in climate. They are perpetually vulnerable to drought, flooding, landslides, and water borne illnesses like cholera. It is a city full of needs in a country that has little in the way of resources.

The Upcountry

It takes some time to get to the upcountry, but it used to take longer. The further you get from Freetown, the bumpier and rockier the road gets. Kadie told us that the road, as bad as it is, is such an improvement over what used to be there. It took us four or five hours to get where we were going. But it used to take more than a day.

You pass through towns, and then the stretch between towns gets longer. And then you pass through villages. Collections of mud huts, with lots of children running around, and a few chickens thrown in for good measure.

Everywhere, you see evidence of agriculture. People drying rice in their front yards. Lots of coffee drying on the ground in the sun. Or palm nuts or cocoa.

And poverty.

I’m hesitant to dwell on the subject of poverty. There is so much more to the people that we meet on these Farm-Direct trips than their economic circumstances. Focusing on what they don’t have can obscure and distort the reality of their lives.

People are very much the same, no matter where you go, or how much money they have. They want good health, safety, shelter, access to food, and a better life for their kids. And they are willing to work hard for those things. They have the same kind of moments of sublime joy, annoyance, boredom, hope, and despair that all of us do.

Lord knows, we’ve seen a lot of poverty in a lot of countries that we go to. But none of us have ever seen anything like we saw in Sierra Leone. I can’t separate it from the story. It is a big part of what we found. And it has left a lasting impact on our psyches.

Look for the Helpers

Everywhere we have ever been, even in the poorest of communities, we find people on the ground that are trying to help. Whether it’s church organizations, NGOs, private industry, or the government, you can see and feel the evidence of people trying to improve lives. Maybe it’s a church run school, or an NGO run clinic. Maybe you see government installed infrastructure, or private investment in the economy.

In the villages we visited in Sierra Leone, there was none of that, with one exception: there were schools. It’s just that there weren’t enough of them to serve all the kids. And it doesn’t help that there is little to no transportation available.

These people are on their own.

Once, many years ago, the NGOs had been there. We saw a lot of faded metal signs announcing projects that had long ago been abandoned or forgotten. Every third or fourth village that we visited had an NGO-drilled well in the center of town.

Side note about those wells: that water still needs to be treated every six months to make it potable. Without that treatment, your odds of coming down with a case of dysentery are pretty good. But the Government is in no position to be able to maintain them all.

It’s not for lack of desire or knowledge. They are a net-importing country for the food and other resources that their people need to live. As an economy, they have very few resources to export. And those that they do have, like diamonds and rutile, are mostly controlled by foreign corporations and extracted in a way that leaves very little of the value in the country. The Government knows what they need to do. They just don’t have the money to do it.

Who We Met

So let’s talk about the people.

We visited many, many villages, one after the other, in our three days upcountry. I was overwhelmed by the number of people I saw of all ages walking around with birth defects. Whether it was cleft palates, club feet, misshapen limbs, or eye diseases, I have never seen so many in one place.

If I had to guess, prenatal nutrition is part of the reason why. The people we met survive on rice and stewed leaves, with the occasional bit of chicken or goat thrown in. And there’s not quite enough, even of those things, to keep them adequately fed. Plus, very few have access to clean water.

We met young children that appeared to be blonde. They weren’t blonde. It’s just that their bodies were not getting enough protein and vitamins in their diet to produce enough melanin for their hair to have color.

And we met an awful lot of widows, women whose husbands were killed in the civil war.

The struggle to survive was palpable in every village we visited. And the only people there to help were Kadie and her family.

One Young Woman

A day and half into our stay upcountry, we were walking through yet another village.

Picture the sight, if you will: four white people, with Kadie and few of her family members, trailed by dozens and dozens of locals and the village Chief. We would start with a crowd of 10, that would be come a crowd of 20, and then 50. And always there were lots and lots of kids. We were the circus, and we’d just come to town.

*Jorge becomes the honorary Chief for the day in one of the many villages we visited.

One young woman stepped out of a doorway and approached me. She tugged at my sleeve. She had an infant on her left hip, and her right breast was exposed. Her eyes were glazed and desperate. And the pain she was in was obvious on her face.

On her exposed breast, there was a cyst about the size of a tennis ball. It was a deep red, caked in puss, with a foul odor, and you could almost see the heat coming off the infection. It was mastitis – a blocked milk duct, but not like any case of mastitis that I had ever seen or heard of.

A long time ago, when our son Dylan was a baby, I had a blocked milk duct and it hurt. In fact, it was searingly painful. But mine looked like a mosquito bite standing next to an elephant in comparison.

This is where that loss of institutional knowledge among grandmothers matters. If these village societies had all of their people, their most important resource, still at their avail, some grandmother would have told that young woman what herbs to pick. She would have shown her how to make a poultice to treat that blocked milk duct long before it became a raging infection that was now threatening her life. But there was no grandmother, and there was no doctor, and there had been no help.

And then we showed up to a place where no outsiders ever come. Not only that, our little merry band includes, very improbably, a doctor. Before he took over production at his family coffee farm in Nicaragua, Jorge was (and still is) a physician. He was able to examine her, and with the help of Kadie’s family translating, instruct her on how to expel the puss. He wrote a prescription for an antibiotic. And, for the final miracle, Kadie had the resources to send someone on a motorcycle to the nearest town, hours away, to pick up the medication, which she paid for.

Jorge told me later that he believes she was within 24-48 hours of succumbing to sceptic shock. What an unfathomably painful and frightening way to die. And what would have happened to her baby?

The odds of her intersecting with us were infinitesimal. We weren’t even scheduled to be in that village. We just got invited to come see yet another coffee farm by an eager farmer, and we couldn’t bring ourselves to say no.

Now, even all these months later, I cannot shake the image of her face or her baby from my mind. For months, we didn’t know what happened next, and we were haunted by possibility that we were too late. But I have good news to report! Bob and had dinner with Kadie in Chicago recently, and she told us that the young woman made a full recovery.

Because we were there, she had a chance. We wouldn’t have there been but for Kadie. And Kadie was there for the coffee farmers.

The Coffee

Which brings me, at long last, to what we found in the fields.

I wish I could say there was good news. But the condition of the coffee farms was as grim as the poverty. Again, we have never seen anything quite like it. Every single farm we walked – and we walked 12-14 a day – had the exact same problems.

Once upon a time, there had been coffee and coffee farmers. People who actually understood and practiced the proper agronomy. What’s left today is like a distant memory of a functioning farm. There are still coffee trees that still produce some cherries. But the problems are vast.

When you walk into the forest, you see coffee plants that haven’t been pruned in years, maybe never. Some are 12-14 feet high, and they are sickly looking with sparse branches. The forest canopy, which should provide between 40-50% shade, completely covers the sky.

That, in turn, has created the ideal environment for pests and diseases. The plants are covered in spiders and ants. In fact, they have to pick in the morning because the fire ants get very aggressive in the afternoon. The insects attack the coffee cherries. There wasn’t one I saw in all the fields we walked that didn’t have insects burrowed inside the beans. And the plants were sick.

None of the farmers knew what variety of coffee they were growing. Based on the way the plants looked, Jorge’s best guess is that it’s a mix of Liberica and Robusta. They don’t know anything about fertilizing or composting, and it shows in the health (or lack thereof) of the soil.

All they know about farming is that you have to “brush” the fields… basically, clearing weeds from around the plants. And you have to pick the cherries.

But they don’t know how, what, or when to pick. So they pick everything: the fruit that has become rotten on the branch, along with the red ones, along with the green ones. And they don’t so much pick as they strip the beans off the branches in one long swoop. That usually breaks the branch, but if even if it doesn’t, it strips away the next year’s bud, which is next season’s crop.

Every year they harvest less coffee. And every year, they get paid less for it.

All of the institutional knowledge about coffee is gone.

Drying

It doesn’t stop there. They don’t have the infrastructure or, often, the access to water to do a washed coffee process, which is how most of the coffee we buy is produced.

So, they do Naturals, which means they dry the cherries naturally in the sun with their fruit on. Naturals have really gained in popularity in the last decade, and there are some amazing Natural coffees on the market.

Typically, when doing Naturals, you would float the coffee in water first to get rid of the underripe and overripe cherries (which sink). But they don’t do that. They dry the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Coffee also starts fermenting the second it is picked, which is why it so important to get the cherries to the drying beds as soon as possible. But no one taught the farmers how to process. And so, they might leave their coffee in a sack on the field for a day, or overnight as it starts to rot, completely ruining whatever character was left in the bean.

They spread their coffee out, usually straight on the ground where even more insects can get at it. But not just insects. We saw chickens, dogs, and other livestock walking through the dried coffee. They might be drying their coffee next to their cooking fire, or where they burn their trash.

The thing to know is that coffee is hydroscopic, which means it absorbs everything in the air around it. I don’t think “chicken poop” or “burning plastic” are flavors that will catch on any time soon.

It’s heartbreaking. And so demoralizing. And sadly, Jorge was the one who had to deliver the bad news. Time and time again, he was the one to look into those faces full of hope that we would buy their coffee at a good price and tell them that their production methods weren’t working. By the end of each day, we were all exhausted, but no one more than Jorge.

We want to learn

Every single farmer we talked to asked us, in fact, begged us for one thing: access to knowledge. And there’s a lot of information that Jorge shared. But implementing his suggestions is impractical when you consider how much duress these producers are under. They can’t afford to hire help for their farms. They can’t possibly work all the hectares that they have by themselves as it is, let alone adding new steps and more processes. And every year, they get paid less.

Many have switched from growing coffee to adding some cacao to their fields. But they don’t know any more about growing cacao than they do about coffee, and that crop is in terrible shape as well. They are working as hard as they can. The physical toll of the work is brutal. But it’s as if they are trapped in a downward spiral, not able to realize any real benefit from their labor.

Who’s Buying It?

You might wonder where all of this terrible coffee is going. The answer is to the Middle-East, where it is roasted almost to the point of being burned. And then all kinds of spices are added to the mix like cardamom and cinnamon. It’s not a taste that most of us would recognize as coffee. But it is a growing market. Someone is making money on the coffee that’s being grown in Sierra Leone. But itsn’t the farmers.

So Where Does That Leave Us?

At the start of this story, I talked about hope being a seed, not unlike a coffee bean. You have to plant it, tend it, feed it, and nurture it. But if you do that, and you have patience, it can grow into a plant the produces a crop that can sustain you.

So where’s the hope here, when everything looks so bleak?

One answer: Kadie.

When she contacted us, she knew next to nothing about coffee. In fact, she rarely drinks it at home. But she walked field after field with Jorge. And she listened carefully as he explained the steps that are necessary to bring the coffee back to life. She absorbed all of that information like a hydroscopic coffee bean.

By the fourth or fifth farm, Kadie was telling the assembled farmers that they need to start managing their shade better and pick only the red cherries. By day two, she was telling them about building African Drying Beds that would create better air flow and keep the cherries away from the livestock and the insects, and thus improve their quality.

By day three, she was hatching a plan.

Model Farm?

It’s not in Kadie’s nature to shrug her shoulders at impossible situations and walk away. She is determined to have an impact.

In a few years, once her kids are through college, she is going to retire from her job and move permanently back to Sierra Leone. She began to get the idea that if she could start a model farm using the proper practices, it could become a laboratory to train some of these producers and increase their quality.

She would start by focusing on some of the “low hanging fruit,” (please forgive the pun). Better shade management is something that can be accomplished with a little training. Teaching farmers to pick only the red cherries is a good start. Teaching them, and maybe even helping to fund them in building African Drying beds could also drastically improve their quality. She is looking to figure out a way that she can make those kinds of small changes financially rewarding for the farmers, as an incentive to do more.

In turn, they could train their neighbors.

And if they start producing quality coffee at a high enough volume, OBIIS will be there to buy it on behalf of BIGGBY COFFEE at a fair, sustainable price.

It is a long shot, and will require a major lift, lots of luck, and very hard work. But what if it works? She will change the world and the economic fortunes for the people in countless villages in the upcountry in Sierra Leone. And she will help develop a brand new lucrative hard currency export crop for her country, which so desperately needs it.

Where do we fit in?

For now, there’s no coffee to buy. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to do. Our OBIIS team is committed to supporting Kadie on this journey with whatever knowledge and technical expertise we can provide. Undoubtedly, she’ll be doing the heavy lifting. But we’ll be with her every step of the way to the best of our abilities.

When you meet Kadie, you’ll understand why. She’s one of the most dynamic, compelling and kind people I have met in a life that has been blessed with many such meetings. And she is doggedly determined.

The challenge ahead of Kadie may be daunting, but my bet will always be on her.

*Our last day in Sierra Leone, Kadie set up a meeting with Dr. Bouku, the Minister of Agriculture for Sierra Leone.

CODA – An Ace in the Hole?

As it happens, Sierra Leone has something in the world of coffee production that no other country has. There is a native Sierra Leonean variety of coffee called Stenophylla. It has been hailed by some scientists as coffee’s great hope in the age of climate change. It is both drought and heat resistant in a rapidly changing world. And it’s hardy and more pest resistant like its cousin, Robusta.

I’ve personally never tasted it, and it isn’t grown commercially. We have no idea what kind of coffee it produces. But the agricultural ministry in Sierra Leone has been doing a lot of research and has developed (and patented) a varietal of Stenophylla that it thinks could work in the field.

They are launching their Stenophylla project just as Kadie is hatching her model farm plan. I don’t know if the two things will come together. But I know that Kadie can hear opportunity knocking.

We can’t wait to see what happens next.